By Dr. Dax Ovid, director of education programs at Call of the Sea

Have you visited the ocean before? Whether you see the ocean regularly or not, the impact of the ocean on our climate and planet is too profound to ignore in K-12 environmental and outdoor education. Learn below why Call of the Sea strives everyday to get classrooms out on-the-water.

Walking down the US Army Corps of Engineers Bay Model Pier, 3rd grade students from Ford Elementary in Richmond, CA were chatting with anticipation of boarding the boat on a Friday in mid-April. One student pointed to the water, “Look, it’s the ocean!” Soon, she would be seeing and feeling a raised relief map of California, noticing the many rivers flowing into San Francisco Bay, and wondering exactly how many rivers deluged fresh water into our local estuary and where the bay became the ocean. Another student started off on the boat by sitting down and staying still. “I’m scared,” she said as we pulled away from the dock. “What are you scared of?” I asked. “That an animal is going to jump on the boat.” I shared that I saw dolphins jumping next to the boat, but I’ve never seen an animal jump on the boat. She smiled.

A Blueprint on Environmental Literacy by the State Superintendent of Public Instruction Environmental Literacy Task Force states, “An environmentally literate person has the capacity to act individually and with others to support ecologically sound, economically prosperous, and equitable communities for present and future generations. Through lived experiences and education programs that include classroom-based lessons, experiential education, and outdoor learning, students will become environmentally literate, developing the knowledge, skills, and understanding of environmental principles to analyze environmental issues and make informed decisions.” This definition was informed by the Ocean and Climate Literacy Principles, and the history of the development of Ocean Literacy principles includes a collaborative effort with scientists and educators from around the world. We’re standing on the shoulders of teams of giants when it comes to environmental literacy. But once you read the Blueprint’s definition of an environmentally literate person, the ocean disappears. Meanwhile, the ocean is prominent in the California Science Framework.

Although over 70% of Earth is ocean, nearly 100% of most humans’ lived experiences are terrestrial. When it comes to designing classroom-based lessons and outdoor learning, land is the most accessible platform for experiential education. It’s easy to overlook ocean environmental literacy, especially for landlocked residents with little to no sea experience. An environmentally literate person is making informed decisions based on “lived experiences, classroom-based lessons, experiential education and outdoor learning.” If students’ experiences and lessons are land-biased, then students are missing the wonders and the mystery of 70% of our planet–largely uninhabited, unexplored, and considered uninhabitable…

While most consider the ocean to be uninhabitable, Lawrence Hall of Science is challenging students to design a city on the water for their summer camp, City Engineers. Imagine design camps informed by direct experience of the bay and ocean.

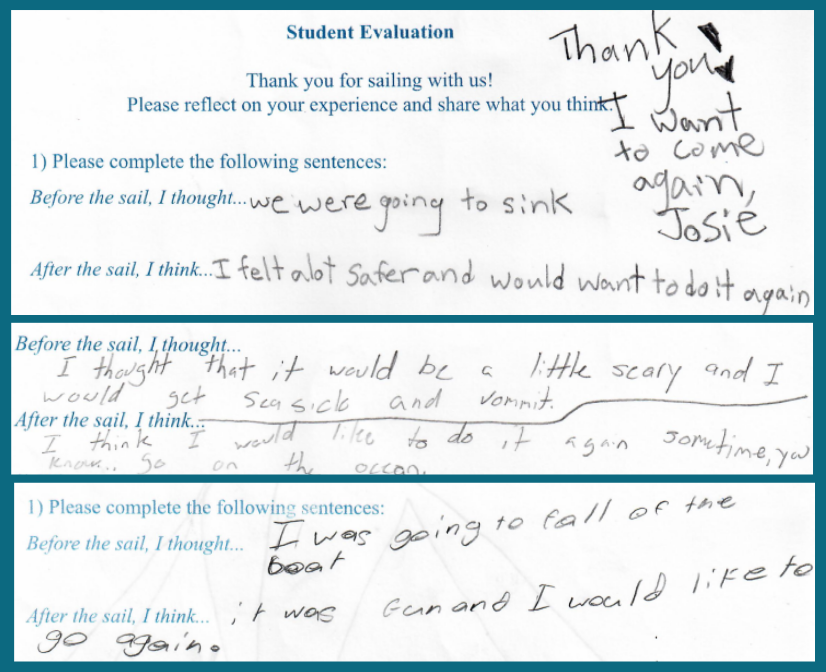

Teachers frequently share it can be an uphill battle to make on-the-water field experiences happen. One teacher said she had to fight with her district 3 years ago to take her class for their first on-the-water educational experience. When I asked her why she had to fight, she said there were concerns about safety for on-the-water programs. I can imagine the same concern being raised before about taking students outside the classroom, stalling teachers’ demand for outdoor educational experiences. It’s like the student afraid an animal would jump on the boat. Preoccupations of the risks of being on a boat can only be assuaged through lived experiences of the wonder, joy, and feeling of an ocean breeze.

Beyond concerns for safety, there are also legitimate concerns about access to coastal and on-the-water field experiences. Consider how far (and how long) you have to drive to see the coast and the ocean. UCLA’s 2017 Policy Report Access for All lists cost as the determining factor. If you can’t drive there and back home in a day trip, you’ll have to find a place to spend the night, and coastal hotels do not have a reputation of affordability. The Coastal Commission has a strategic priority of providing low cost coastal accommodations, and they list Residential Outdoor Education Facilities (like the environmental education non-profit Call of the Sea) in the 2019 Explore the Coast Overnight Report. Given the information and suggestions compiled in these reports, we can start working collectively to support coastal access and routine, on-the-water educational field experiences for all.

The future of our planet depends on the state of our ocean. Given the untapped potential in educational opportunities provided by the ocean, how can schools and districts take advantage of existing resources to foster ocean environmental literacy for their students?

-

Challenge students to ask questions about their local watershed and the one, largely unexplored ocean: connecting all our continents, influencing our climate, and supporting a diversity of life and ecosystems (see Ocean Literacy Principles).

-

Engage in professional learning opportunities that fulfill California NGSS with coastal and water-based field experiences connected to classroom curriculum (e.g. Monterey Bay Aquarium, NOAA, Project WET)

-

Foster ocean environmental literacy and stewardship by connecting local actions to global impacts (e.g. NOAA’s Restoration Projects and the Coastal Commission’s Schoolyard Cleanups).

-

Join communities of educators committed to improving ocean literacy and marine science education (e.g. National Marine Educators Association)

-

Explore on-the-water programs statewide to observe natural phenomena, track cause and effect, and engage with natural systems and processes in the field (e.g. Call of the Sea can host classes on large sailing vessels, Treasure Island Sailing Center has small sailboats, and SeaTrek has kayaks in San Francisco Bay or Los Angeles Maritime Institute in San Pedro Bay. California State University, Northridge Aquatic Center at Castaic Lake is leading a group of other CSU boating centers into ocean environmental literacy learning). If your school or district has limited funding for field experiences, ask about scholarships and other aids.

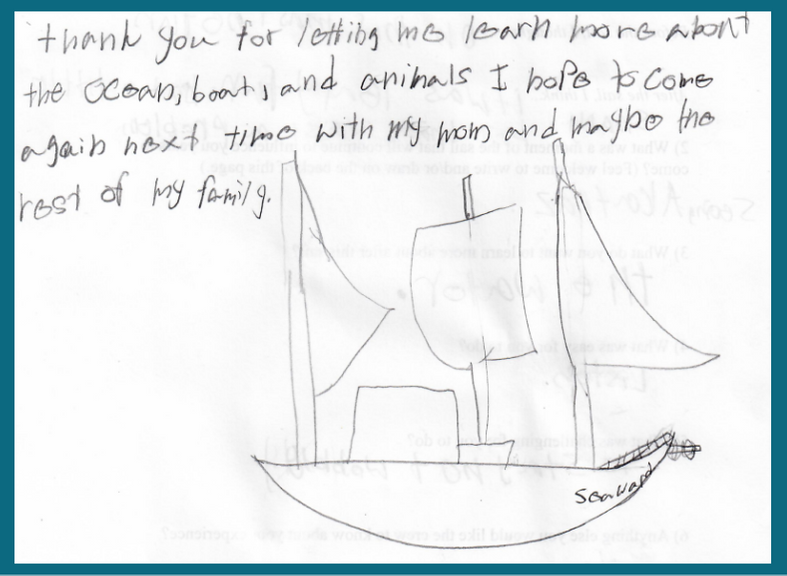

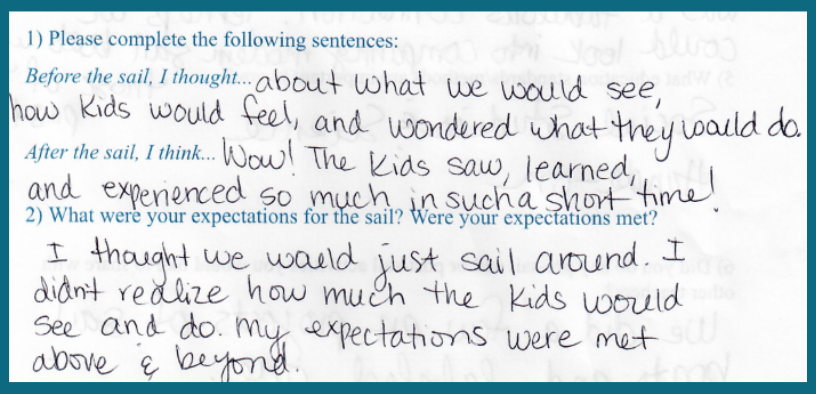

The ocean is immense and so are the learning opportunities. We see from student evaluations how on-the-water natural phenomena inspire wonder, awe, and further questioning. Reach out to an organization providing on-the-water field experiences and dive into the possibilities for your class, your district, and our future environmental stewards for both land and sea.

The first step is equitable access to coastal and on-the-water field experiences. The next step, in conjunction with the first, must facilitate inclusive and culturally-relevant pedagogical practices for science, engineering, and environmental education for all.

A special thank you to Capt. Kurt Holland, Capt. Stephen Taylor, and Matt Grigorieff for feedback on this article.

Students First

Experiential Learning at Our Core

Maritime Expertise

Sustainability On & Off the Water